A portrait of Prince taken by Lynn Goldsmith (left) in 1981 and 16 silk-screened photos Andy Warhol later created utilizing the photograph as a reference.

Assortment of the Supreme Courtroom of the US

conceal caption

toggle caption

Assortment of the Supreme Courtroom of the US

A portrait of Prince taken by Lynn Goldsmith (left) in 1981 and 16 silk-screened photos Andy Warhol later created utilizing the photograph as a reference.

Assortment of the Supreme Courtroom of the US

In a 7-2 vote on Thursday, the U.S. Supreme Courtroom dominated Andy Warhol infringed on photographer Lynn Goldsmith’s copyright when he created a collection of silk display screen photos based mostly on {a photograph} Goldsmith shot of the late musician Prince in 1981.

The high-profile case, which pits an artist’s freedom to riff on present artistic endeavors in opposition to the safety of an artist from copyright infringement, hinges on whether or not Warhol’s photos of Prince rework Goldsmith’s {photograph} to an awesome sufficient diploma to stave off claims of copyright infringement and due to this fact be thought of as “honest use.” Below copyright regulation, honest use permits the unlicensed appropriation of copyright-protected works in particular circumstances, for instance, in some non-commercial or instructional instances.

Goldsmith owns the copyright to her Prince {photograph}. She sued the Andy Warhol Basis for the Visible Arts (AWF) for copyright infringement after the muse licensed a picture of Warhol’s titled Orange Prince (based mostly on Goldsmith’s picture of the pop artist) to Conde Nast in 2016 to be used in its publication, Vainness Honest.

Goldsmith did license using her Prince photograph to Vainness Honest again in 1984, when the journal commissioned Warhol to create a silkscreen work based mostly on Goldsmith’s photograph after which used a picture of Warhol’s piece to accompany an article they ran that yr in regards to the musician. However that was just for the one-time use of the picture. Based on the Supreme Courtroom opinion, the journal credited Goldsmith and paid her $400 on the time for its use of her “supply {photograph}.”

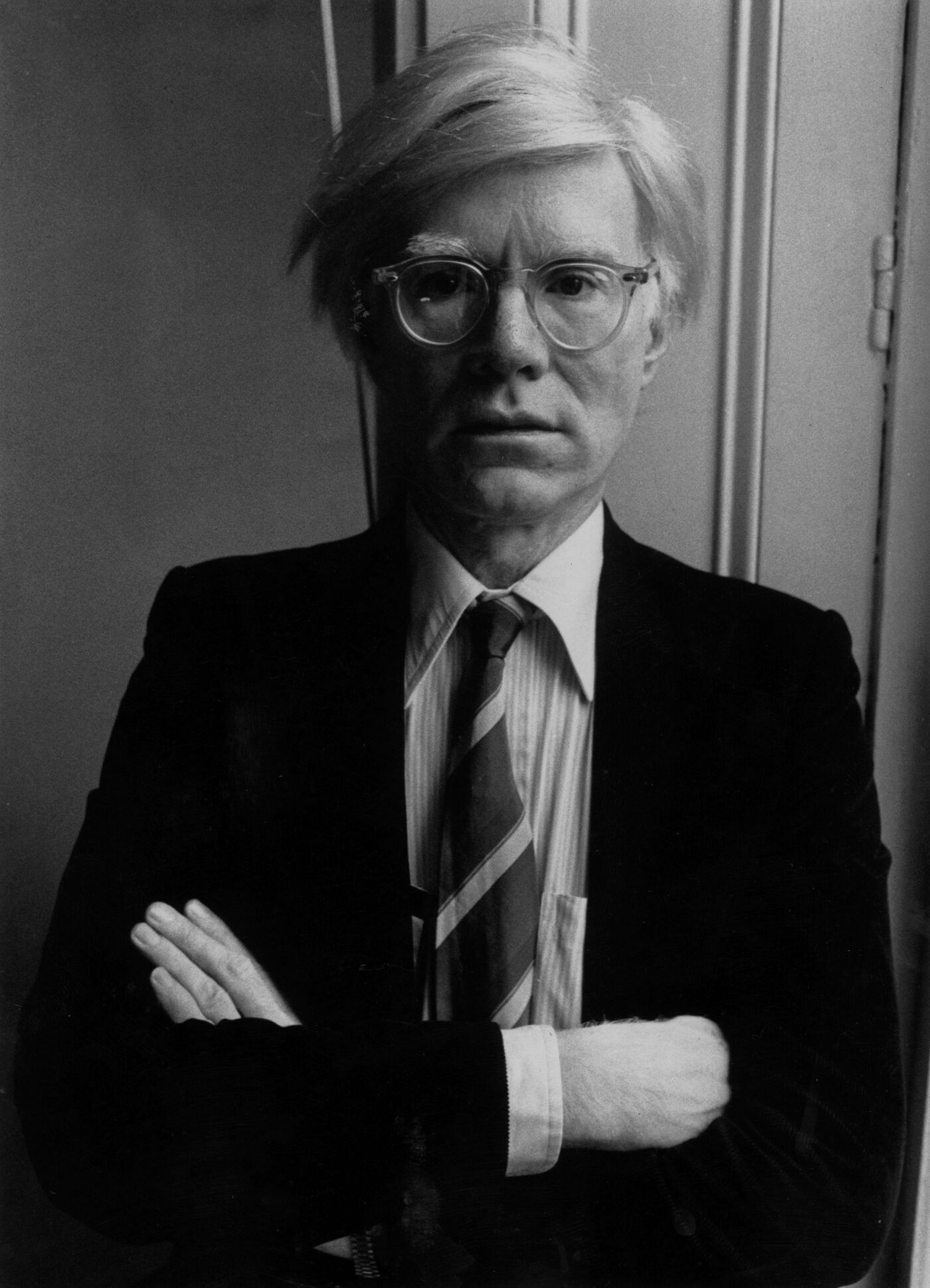

Andy Warhol pictured in February 1980.

John Minihan/Night Commonplace/Getty Photos

conceal caption

toggle caption

John Minihan/Night Commonplace/Getty Photos

Andy Warhol pictured in February 1980.

John Minihan/Night Commonplace/Getty Photos

Justice Sonia Sotomayor delivered the opinion of the court docket.

“Goldsmith’s unique works, like these of different photographers, are entitled to copyright safety, even in opposition to well-known artists,” wrote Sotomayor in her opinion. “Such safety consists of the suitable to organize by-product works that rework the unique.”

She added, “Using a copyrighted work might nonetheless be honest if, amongst different issues, the use has a goal and character that’s sufficiently distinct from the unique. On this case, nonetheless, Goldsmith’s unique {photograph} of Prince, and AWF’s copying use of that {photograph} in a picture licensed to a particular version journal dedicated to Prince, share considerably the identical goal, and the use is of a business nature.”

A federal district court docket had beforehand dominated in favor of the Andy Warhol Basis. It discovered Warhol’s work to be transformative sufficient in relation to Goldsmith’s unique to invoke honest use safety. However that ruling was subsequently overturned by the 2nd U.S. Circuit Courtroom of Appeals.

Justice Elena Kagan’s dissent, shared by Chief Justice John Roberts, acknowledged: “It would stifle creativity of each type. It would impede new artwork and music and literature. It would thwart the expression of latest concepts and the attainment of latest information. It would make our world poorer.”

Joel Wachs, President of The Andy Warhol Basis for the Visible Arts, shared the 2 dissenting justices’ views in an emailed assertion the muse despatched to NPR.

“We respectfully disagree with the Courtroom’s ruling that the 2016 licensing of Orange Prince was not protected by the honest use doctrine,” wrote Wachs. “Going ahead, we are going to proceed standing up for the rights of artists to create transformative works below the Copyright Act and the First Modification.”

Authorized consultants contacted for this story agreed with the Supreme Courtroom’s resolution.

“If the underlying artwork is recognizable within the new artwork, then you definitely’ve obtained an issue,” stated Columbia Legislation Faculty professor of regulation, science and know-how Timothy Wu in an interview with NPR’s Nina Totenberg.

Leisure lawyer Albert Soler, a companion with the New York regulation agency Scarinci Hollenbeck, stated that the business use of the {photograph} again in 1984 in addition to in 2016 makes the case for honest use tough to argue on this occasion.

“One of many components courts take a look at is whether or not the work is for business use or another non-commercial use like schooling?” Soler stated. “On this case, it was a collection of works that have been for a business goal in accordance with the Supreme Courtroom, and so there was no honest use.”

Soler added the Supreme Courtroom’s ruling is prone to have a big effect on instances involving the “sampling” of present artworks sooner or later.

“This supreme court docket case opens up the floodgates for a lot of copyright infringement lawsuits in opposition to many artists,” stated Soler. “The evaluation goes to come back down as to whether or not it is transformative in nature. Does the brand new work have a special goal?”

Wu disagrees in regards to the ruling’s significance. “It is a slim opinion centered totally on very well-known artists and their use of different individuals’s work,” Wu stated. “I do not assume it is a broad reaching opinion.”