Textual content and Pictures by Asad Sheikh.

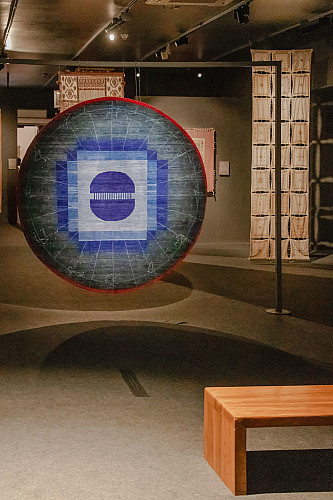

Nakshatra, Fibre cowl, handwoven Indian wool with hand-knotting, abrash dyeing and hand-embroidery. Designed by Ashiesh Shah – Atelier with Jaipur Rugs.

Sutr Santati: Then Now Subsequent, the exhibition that was showcased within the capital, introduced the narrative of India by way of its textiles. Every one of many about-100 textiles on view, from varied areas of the nation, displayed a plaque with an inventory of names. These highlighted not solely the designers, textile artists and revivalists concerned within the creation of every of the works, but in addition, importantly, the artisans concerned — the embroiderers, weavers, dyers and printers.

The exhibition — that concluded in late October — proved that textile craftsmanship within the nation continues to be a vibrant entity. However, the best way we all know or see it does bend to the desire of commerce. Traditionally, grander strategies and supplies — than those on show at Sutr Santati — had been usually used to create one-of-a-kind items below the artwork of patronage. However in a globalised, and machine-powered market, these strategies have change into extra streamlined, usually to suit the alternatives of the patrons.

With commerce out of the equation, designers, artists and artisans, who participated within the exhibition, might extra freely discover present-day strategies and develop newer types of textile manipulation to additional the concept of Indian craftsmanship. And so, the exhibition assortment, most of which was specifically commissioned for the present, didn’t mimic textile samples discovered encased in museums from India’s colonial and pre-colonial eras. It innovated, by introducing new motifs, supplies, and workaround methods to attain the same diploma of complexity within the closing materials, leaving us with new hope for the way forward for textile revivalism.

Excerpts from a dialog with Lavina Baldota, textile revivalist and curator of Sutr Santati….

How do you intend to create consciousness about India’s textiles, particularly among the many youthful era?

The thought is to take the dialog about textiles past apparel. Usually, we consider textiles as solely associated to one thing we put on. However in our nation, textiles have all the time been an enormous a part of our artwork. They’ve been an enormous a part of our tradition. We gown our gods in textiles, we’ve got Pichwai work…. There has all the time been such a superb line between the craft and the artwork. I need to carry again that sensibility and provides it a extra modern context in order that right this moment’s era turns into conscious of the strategies. And I need to make it interesting to them — in order that they’re excited to place textiles up of their properties, possibly. Consciousness creates appreciation, and appreciation will create aspiration. That’s the entire concept.

High left: Discover the Hidden Knots, Merino wool scarf with embroidery by Rahul and Shikha, created by Muzamil, Maheshwar, Madhya Pradesh and Jaipur, Rajasthan; Unity in Range, hand embroidery by a number of artisans, Kutch, Gujarat.

High proper: Naga Raincoat, Ashiesh Shah — Atelier X Cane Idea.

Backside left: Sarnath, mulberry silk (warp) panels and viscose (weft) with zari. Designed by Asha Madan – Good Earth and created by Haji Kasim Mohammed Ishaque, Benaras, Uttar Pradesh.

Backside proper: Treescape, cotton warp with discarded cotton and silk within the weft. Naturally dyed indigo and madder. Designed by Ashita Singhal and Balbir Singh, New Delhi.

What half does Sutr Santati have in your imaginative and prescient?

Textiles have been such an vital a part of our freedom motion, the Swadeshi motion, and our tradition. So, my first Sutr Santati exhibition was on Mahatma Gandhi, and khadi was a giant component of that. This time as nicely, to maintain the identical mandate and take it ahead, we used solely indigenous yarns. You possibly can see what number of forms of yarns we’ve used on this exhibition, they usually’re all from the area the work was achieved in. For instance, a Gujarati artisan would use Kala cotton, and Kandu cotton could be utilized in Karnataka. There are such a lot of completely different sorts of yarns that individuals are not conscious of — from camel hair and goat hair to various kinds of wools and wild silks. And utilizing eco-friendly dyes was additionally an important a part of this exhibition in order that you don’t hurt the atmosphere while you create.

Traditionally, patronage performed an vital position within the flourishing of a number of crafts. What has modified at the moment with fast consumerism and fast-paced manufacturing?

The thought of sluggish consumerism is essential to me as a curator. Select fewer issues, however perceive how they’re made. And in addition to, textiles are fairly long-lasting. They’re not in vogue or out of vogue ever, proper? I imply, they’re a heritage. And in the event you lose that craft, you’ll lose the tradition. So you will need to have youthful minds begin fascinated with the truth that you don’t want so many issues.

High left: Kodalikaruppur, sari in cotton, zari and pure dyes. Handwoven and hand-block printed. Chennai and Machilipatnam, Tamil Nadu and Andhra Pradesh.

High proper: Patan Srinath Ji, wall panel in silk. Handwoven jamdani designed by Gaurang Shah, Patan, Gujarat.

Backside left: Mughal Flowers, dupatta in handwoven silk and zari, by Naseem Ansari — ASHA workshop, Benaras, Uttar Pradesh.

Backside proper: Hanging by a Thread, superb cotton in a number of counts and zari threads, by Lakshmi Madhavan and Arvind Vijayan, Balaramapuram, Kerala.

Textile revival comes with its personal set of challenges. Attempting to seize and recreate the precise type of creating a bygone textile won’t all the time be doable. Have you ever confronted any such challenges?

Sure, completely. The revival of something that has been misplaced is so tough. The Kodalikaruppur sari that was displayed within the exhibition, as an illustration, is within the means of revival. It’s been such an extended path to get again that very same crimson color that was initially used. The atmosphere has modified, and the water it was once washed in has modified. The standard of the zari threads has modified. The motifs on the sari that had been hand-painted have been changed with hand-block printing. We’ve got to be acutely aware to not lose the craft. It’s been a really tedious exercise to revive it to its genuine self. So, if we will save a craft from languishing, we should always. Fairly than letting go of it utterly and having no reference to carry it again.

The current exhibition talked about “then, now, and subsequent”. May you share with us what’s subsequent for you, and your wider endeavours by extension?

I need this exhibition to journey world wide and my efforts in the meanwhile are utterly focused on that. We’re collaborating with the Museums Victoria in Melbourne, and the exhibition is scheduled to be mounted from April to July 2023. I need this to be seen as a result of it’s good to take a neighborhood dialog international. I need folks overseas to grasp our tradition and interact with it.